This week we are turning all the way back to the beginning of the United States as we commemorate the death of Crispus Attucks, the first man slain at the Boston Massacre. The biographical information included in the cookbook is relatively brief, but Sue Bailey Thurman does mention that a prominent high school in Indianapolis bears his name. As such, the Indianapolis Council that submitted the recipe for this “johnny cake.”

When I (Kayleigh) read the title of this dish, I recognized it (I thought) as another name for hoe cakes, which my grandma made when I was growing up. Her hoe cakes were sort of like a pancake made with cornmeal, fried in oil. We Googled it and the internet seemed to agree. However, this recipe was not really like that at all, but rather a sweet cornbread that could be enjoyed at any time of the day.

Crispus Attucks and the Boston Massacre

For years, American colonists had been growing increasingly dissatisfied and hostile towards the British government, to which they were subject. Policies like the Stamp Act (1765) and the Townshend Acts (1767) implemented taxes on the American colonies, yet they had no representation in Parliament. In other words, the British government was charging colonists money without allowing them a say in the policies that governed them. Even the “elected representatives” in the colonies, of which there were few and they were certainly appointed by the Crown, were expected to serve King and Queen’s interests first and foremost. In 1770 there was a series of confrontations between British loyalists, soldiers, and colonists, which resulted in property damage and even the death of a young boy.

On March 5th, 1770 a group of colonists in Boston were involved in an altercation with British soldiers, resulting in the death of four colonists. Though there were nearly two hundred eyewitness accounts of the events, many were contradictory and therefore many of the specifics of the event remain unclear.* However, the general narrative that you may have learned in grade school remains uncontested. There was a soldier stationed outside of the Boston Customs House and a few colonists showed up and instigated a verbal confrontation. Eventually the soldier fought back, hitting one of the colonists with his bayonet. From there, things continued to escalate – more colonists and soldiers arrived, the town alarm was rung, and colonists began throwing rocks, snowballs, and eventually beat some of the soldiers with clubs – until one of the soldiers fired into the crowd. Once one had been fired, more shots from the soldiers went into the crowd until five colonists were dead and six injured.

Crispus Attucks was the first to be shot, followed by Samuel Gray, James Caldwell, Samuel Maverick, and Patrick Carr (he died from his injuries after the other four). Despite the outrage over these men’s deaths, the nine soldiers brought to trial were not convicted of murder. Seven were found not guilty and two were convicted of the lesser charge of manslaughter. The future president of the United States, John Adams, defended the soldiers because he believed that they deserved a fair trial. He, like other colonial leaders, was resistant to British policies, but did not want the colonies to devolve into mob rule, which he believed the events at the Customs House to be.

Despite the jury’s view that most of the soldiers were not legally culpable, the events of that day would remain a rallying point for colonists who felt that the British were exploiting them. As Adams himself would later say, “The 5th of March 1770, ought to be an eternal warning to this nation… on that night the foundation of American independence was laid.”** In other words, even though the event itself was not legally a “massacre,” its memory as such had important and lasting political significance.

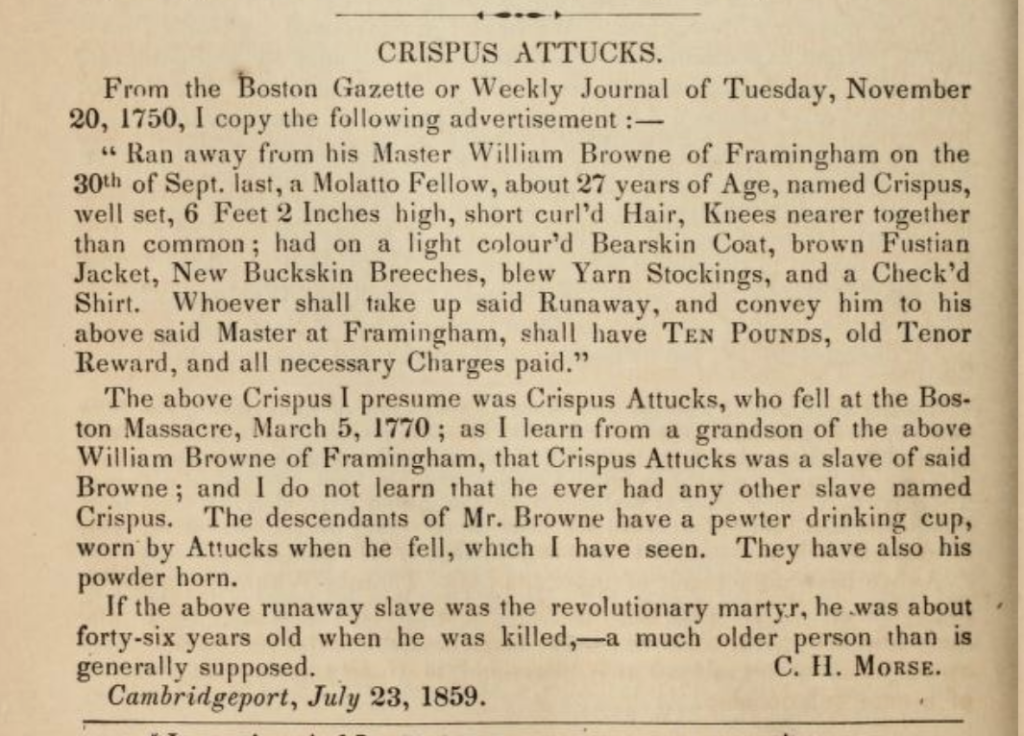

Like the massacre itself, Attucks’ place in American memory is inspired more by its power in the narrative of American freedom than the historical reality. Very little is known about Attucks’ biography. Reports from the time indicate that he was mixed-race, most likely African American and Native American, and he was born a slave around 1823 in Framingham, MA. When he was 27, he ran away and became a seaman in Boston, which was one of the few trades available to African Americans. Some scholars speculate that his profession was the reason that he was involved in the massacre. According to Historian Douglas Egerton, Attucks was at a pub on the evening of March 5th when a soldier came in inquiring about part-time employment. Sailors’ wages were so low that they often needed second jobs, creating tension between them and the large number of soldiers arriving from Britain. That night Attucks and others harassed the soldier looking for work and chased him out of the bar. During the soldiers’ trial John Adams stated that Attucks was the leader of the group that harassed the soldier at the Customs House.***

After the initial flurry of activity surrounding the Massacre and the trial, there were limited reports about Attucks, and the events in Boston more generally. When he was included in the retellings, his race was often hidden, downplayed, or possibly unknown to the author. However, beginning in the latter half of the 19th century, Crispus Attucks became a major figure in African American history. His martyrdom was used as a symbol of the patriotism and sacrifice of black people in American history. Sue Bailey Thurman captures this in the cookbook when she writes that Attucks was “the first American to to fall in the revolutionary struggle.”

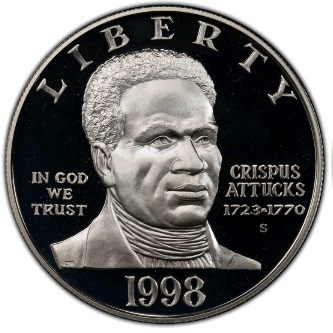

Evidence of Attucks’ growing popularity, for both African American history and American history more generally, is is seen in the US government’s choice to feature him on their currency. In 1998 the United States mint issued a coin commemorating black Revolutionary patriots and the 275th anniversary of Attucks’s birth. The coin shows a ‘‘portrait’’ of Crispus Attucks, even though no actual image of Attucks exists.

The Dish:

Making the Johnny Cake was rather uneventful. The instructions were straightforward and the cooking went according to plan.

Ingredients

3/4 cup all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1/2 teaspoon salt

1-1/4 cup corn meal

2 eggs, beaten

1/4 cup white distilled vinegar

1 cup sweet milk

4 tablespoons melted shortening

The instructions did not say to preheat the oven, but we decided to go ahead and set it to 400, which was listed in the final step.

The first instruction was to sift the dry ingredients together and then mix in the cornmeal. Then, we had to combine the eggs, vinegar, milk, and shortening (we used butter) in a separate dish, and then add that to the dry ingredients.

We added the batter to a skillet and then put it in the oven for the instructed 30-35 minutes. It was done right on time, so we pulled it out to cool.

It was really tasty and had a nice balance between salty and sweet. We ate it that evening with dinner and then the next day for breakfast and a snack!

Final Thoughts

We enjoyed this recipe and learning about the role of memory in American History. Even though we don’t often commemorate the Boston Massacre, it was nice to revisit the revolutionary period and be reminded of the radical figures that contributed to the creation of a new nation.

Notes

*Hinderaker p. 1

**Quoted in Neil York, John Adams to Matthew Robinson, March 2, 1786, in Charles Francis Adams, ed., The Works of John Adams

***From Forgotten Founder to Indispensable Icon: Crispus Attucks, Black Citizenship, and Collective Memory, 1770–1865 by Mitchell A. Kachun, Journal of the Early Republic 29, no. 2 (2009): 249–86.

Information on the first painting can be found here: https://www.teachushistory.org/second-great-awakening-age-reform/resources/boston-massacre-champney

This History Channel page provides a succinct summary of all of the available information about Attucks, with links to sources: https://www.history.com/news/crispus-attucks-american-revolution-boston-massacre

Kachun, Mitch. “From Forgotten Founder to Indispensable Icon: Crispus Attucks, Black Citizenship, and Collective Memory, 1770-1865.” Journal of the Early Republic 29, no. 2 (Summer, 2009): 249-286.

Hinderaker, Eric. Boston’s Massacre. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (Cambridge, MA), 2017.

York, Neil Longley. The Boston Massacre : a History with Documents. Routledge (New York, NY), 2010.