To Honor the musicians this week we made a stunning Minnehaha Indian Egg Bread. This section of the cookbook made mention of countless iconic Black musicians and artists of the late 19th and early 20th century, including: Harry Burleigh, composer and baritone; Nathaniel Dett, Canadian-American composer, organist, pianist, choral director at the Hampton Institute, and music professor; Maude Cuney Hare, pianist, musicologist, writer, and African-American activist; and finally, two sculptors Edmonia Lewis and May Howard Jackson. While all of these are worth learning about, we’re going to focus on two musicians for which the egg bread was chosen: S. Coleridge Taylor and Madam Lillian Evanti.

The recipe itself turned out to be a challenge, as Abena’s allergies required that Kayleigh make the recipe herself. Dough. got. everywhere. We’ll tell you more about this below, but for now let’s get to Taylor and Evanti.

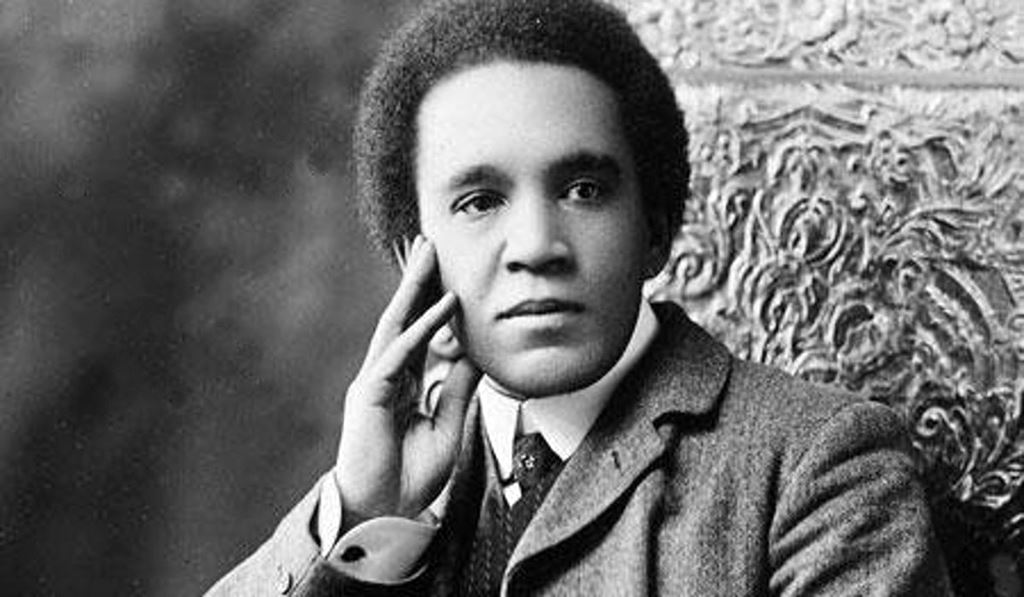

Samuel Coleridge Taylor

First, Samuel Coleridge Taylor, is our first non-American figure to be featured on the blog! Born to an English mother and Sierra Leonean father in 1875 in Holborn, England, Samuel Coleridge Taylor was a composer, conductor and political activist. His father, Daniel Taylor, a doctor, practiced in Croydon, where he met and began a relationship with Alice Martin. Sadly, Taylor left England for a position as Imperial Coroner in Gambia, Martin married a man, meaning Coleridge grew up an mixed-race illegitimate child in a lower-middle class white family.

The historical record is unclear on where Coleridge received his musical influence, but we know he grew up around music. Some suggest his father played the violin and taught him the instrument from a young age. Other sources suggest that it was in Martin’s family that were highly musical and it was here that he became a talented violinist and singer. Either way, Coleridge demonstrated talent and passion for music and so an impressed patron paid his way into the Royal College of Music at the age of 15, where he developed his skills further. Throughout his time at the College, teachers remarked upon the “boy of colour in patched trousers” who so quickly excelled as a violinist, pianist, and composer. He began composing under the guidance of Irish composer Charles V. Stanford, and began publishing his pieces. Not only did his compositions get better and better, Coleridge grew in popularity after he graduated. His debut piece, Ballade in A Minor, earned him the name “genius” by August Jaeger, the well-known music publisher.

Fellow composers lauded Coleridge’s work, with Edward Elgar celebrating him as “far away the cleverest of the young men” and establishing an orchestral commission for him. Further, Coleridge’s composition and political renown reached beyond the borders of the UK, leading to an invitation to the White House from President Theodore Roosevelt. This invitation came during the Jim Crow era when segregation legally ruled in the South and customarily elsewhere, making Coleridge’s visit a moment of national significance.

A unique feature of Coleridge’s compositions came from his intentional embrace of his African heritage in his music, through incorporation of traditional African musical motifs. He studied both African and Caribbean music styles, as well as African American spirituals in an effort to create a diasporic “romantic nationalism.” This meant that his classical music was infused with syncopation and bluesy harmonies, which set his music apart from his contemporaries. Coleridge drew inspiration from his namesake, a famous poet Samuel Taylor-Coleridge, and even utilized poetry in his music. Most famously, and noted in the cookbook, was his cantata trilogy, named The Song of Hiawatha, which included Hiawatha Overture, a section based on a poem by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. This poem evoked the culture of the increasingly marginalized native Americans, which was an object of ethnographic and anthropological interest at the turn of the century.

Despite his success, Coleridge faced multiple financial struggles through his short life. Even at the height of fame Coleridge was still penniless. Not knowing the prominence his cantata trilogy would reach, he sold the publishing rights for fifteen pounds, meaning that he shared in none of the profits made by the 140,000 copies sold before World War I. Despite the fact Coleridge passed away at the age of 37, he composed over 100 works, including an opera, a symphony, many theater scores and chamber music.

It is the second cantata in Coleridge’s The Song of Haiwatha, named “Haiwatha’s Wedding,” that links him to the recipes second honoree: Madam Lillian Evanti. According to the cookbook, Evanti was not only a member of the NCNW but an international concert artist who made a “special trip” to London to hear the performance of the piece. It also states that the tenor Roland Hayes “sung so often and with such poignant beauty” to Madam Evanti, parts of “Haiwatha’s Wedding.” So, she is worth mentioning here, too.

Madame Lillian Evanti

Born Lillian Evans in Washington D.C. in 1890, Evanti grew up in a wealthy and well-educated family. Both of her parents worked as educators in District schools. Her mother, Annie Brooks, taught music, while her father, Wilson Bruce Evans, taught at the same school. Eventually, her father went on to attend and complete medical school at Harvard University in 1891, and went on to teach and become principal of the Armstrong Manual Training School for a decade. Sadly he was unjustly fired and Lillian spent much of her adult life advocating for his reputation, leading to the school being named after him in 1962.

Howard University President Mordecai Johnson presents Lillian Evanti with the Distinguished Alumni Award in Rankin Chapel on Charter Day in 1944. Evan-Tibbs Collection, Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, gifts of the Estate of Thurlow E. Tibbs, Jr.

Lillian attended the District schools and demonstrated skills in art, namely drawing, and began piano and music lessons.Initially, Evanti went on to train as a teacher, and spent several years teaching kindergarten while attending Washington Conservatory of Music, for which she received a scholarship. She sang initially with a group of known group of folk singers, and made her debut in 1915 at New Bethel Church. Eventually she enrolled at Howard University as a music major, from which she graduated in 1924.

In May 1924 she performed her farewell recital in Boston, then set sail for Paris with friend and artist Laura Wheeler Waring to pursue her operatic career. Despite being the “First Lady of Opera in her race,” Evanti deemed the move necessary due to the racism in America that stunted her career opportunities. It was here that Lillian Evans became Madame Lillian Evanti, a combination of her maiden name Evans and her married name Tibbs. In Europe she continued her music studies, adding languages and acting, eventually becoming fluent in five languages. The move to Europe became the launching pad of her international renown, as she become the first African American to sing in a professional European opera company in 1925. Over her career Evanti played over twenty roles including the famous role of Rosina in The Barber of Seville. She also performed in Europe, Latin America, as well as the United States.

After her time in Europe, Evanti returned to D.C and became a founder of the National Negro Opera Company (NCCO), playing in their performances which took place aboard a barge anchored on the Potomac River and attended by roughly 15,000 people. She advocated, too, for a national performing arts center, testifying to a Congressional committee in 1935, all of which led to the founding of the Kennedy Center.

Aside from her operatic achievements, Evanti also excelled as a composer, lyricist, activist, teacher, and goodwill ambassador for the Department of State. As a lover of art, she collected many pieces that live on through the Evans-Tibbs collection curated by her grandson. And as a composer, Evanti expressed her internationalist activism through bilingual anthems dedicated to organizations dedicated to pan-Africanism and honoring newly independent nations like Ghana.

The Dish: Minnehaha Egg Bread

Ingredients

8 cups flour (more if desired)

1-1/2 cubes of butter or 3/4 cups of lard

1- 1/2 teaspoons salt

1 cup hot milk

1 cup sugar

1-1/2 dozen eggs (well beaten)

1-1/2 packages dry yeast

As we mentioned above, this recipe turned out to be sort of a doozy. You may not have noticed at first glance, but this recipe calls for 18 eggs and 8 cups of flour. In other words, this dough was going to be HUGE. We did not realize this until we pulled everything out to get cooking.

Kayleigh was on her own to navigate the characteristically sparse instructions. She has made bread many times before (her sourdough starter predated the COVID lockdown), so she was able to intuit the gaps in the recipe. For example, the first step listed is Knead until bubbles appear, let rise, punch down, let rise again, then shape into loaves. Not only is that five steps in one, but it offers no guidance on how to combine all of the ingredients – do we do it all at once? does the butter or lard need to soften? does the “hot” milk need to boil? We went with yes for all of these.

After bringing the milk to a light boil, I (Kayleigh) let it cool slightly before slowly adding it to the whisked eggs. I added the softened butter and the yeast to this mixture. Before mixing it all together, I let the yeast activate (the gross bubbly picture below). Once the yeast let me know it was ready, I added the flour and used a spatula to combine everything.

Almost immediately, I realized that we might have some problems. The dough was incredibly soft and sticky. I pressed on, adding a bit more flour until everything was combined and then I let it rest. The recipe said to knead until bubbles appear, but I was not sure how that was going to happen without giving the yeast time to rest, so I followed my gut.

After about an hour, bubbles had started to form, so I punched it down and let it rise for another hour.

When I transferred it to the counter it was still so sticky and as I tried to knead it, it got everywhere. It crawled all the way up my wrists onto my forearms, it was all over the countertop, and as I was trying to add more and more flour to keep it from sticking, it got all over the flour container! You can see some of the crime scene photos below.

I managed to get it back into a different bowl for its second rise (the first per the instructions), about an hour and a half, and then punched it down and let it rise again for about an hour. I ended up breaking it into three loaves (the recipe did not specify how many there should be…) and let them complete their final rise while the oven preheated to 400 degrees.

As a reminder, that was all “step one.”

The second step is to put them in the 400 degree oven for 10 minutes and then cut it down to 325 until the bread browns, about 45-50 minutes.

That’s the entire recipe.

The bread rose nicely as you can see in the image below, but it tasted like nothing. Similar to the Mott pound cake, it desperately needed salt and despite the 18 eggs, it was honestly pretty dry. I sliced and froze most of it in the hopes that I can use it for french toast in the future. Unlike the Mott pound cake, I don’t think it would be any good in ice cream.

Final Thoughts

While Madame Evanti and S. Coleridge Taylor were fascinating figures, this recipe was on the whole underwhelming (or overwhelming depending on the point at which you caught Kayleigh). We were excited to be able to bring more Black artists and non-American figures into the blog and look forward to seeing who else is waiting for us in the latter part of the year!

Notes

https://www.classical-music.com/composers/samuel-coleridge-taylor/

https://poets.org/poet/henry-wadsworth-longfellow

https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/who-was-samuel-coleridge-taylor-what-famous-for/

https://anacostia.si.edu/collection/spotlight/madame-lillian-evanti