This was without a doubt our easiest recipe to date. It was also one of the tastiest! The tea is part of a larger entry called “Honoring Pioneer Principals with ‘Afternoon Tea’” There were also Old Fashioned Tea Cakes included, but we decided to only do one of the recipes this week.

As you might recall, our last post was celebrating the birthday of Juliette Derricotte – a tireless advocate for African American students. This week’s figures are also educators, whom Sue Bailey Thurman describes as pioneers. The recipes honor three women, but acknowledge two additional women who were engaged with Black educational institutions. Teaching was not only an important job in the African American community, but a prestigious one as well. Women in particular went to great lengths to pursue necessary training to teach in their communities and, as is evidenced by those discussed below, were integral figures in establishing schools for young African Americans. Both during the Antebellum and post-Civil War periods, African Americans understood that education was critical for their own advancement and as a way to establish their equality with white people. Since they were denied access to schools at every level, they worked with white allies to build their own institutions like the African School in Boston which was founded in 1787!

Pioneers

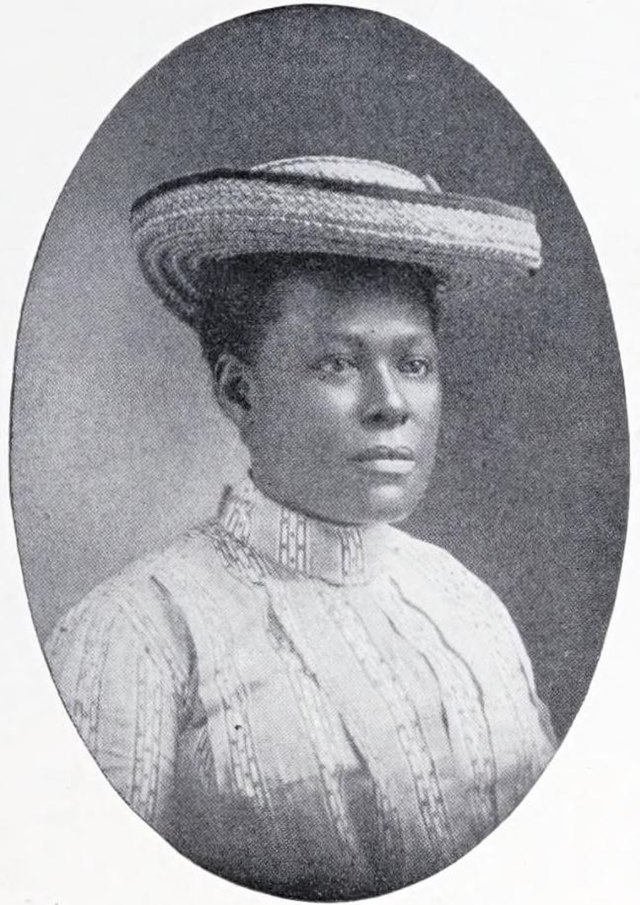

Mary Jane Patterson

Though the exact details cannot be confirmed, scholars believe that Mary Jane Patterson was born into slavery in Raleigh, North Carolina around 1840. The following decade her family moved to Oberlin, Ohio where Patterson enrolled in preparatory coursework for Oberlin College. Oberlin was an integrated and coeducational school. In 1857, Patterson did something truly extraordinary. Instead of following the normal path for women, which would have been enrolling in an abbreviated program, she chose to register for the men’s classical education at the conclusion of which she became the first woman to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree in the United States in 1862. After completing college, Patterson first moved to Pennsylvania and then Washington D.C. to teach at the first public high school for African Americans, Preparatory High School for Colored Youth. This was later renamed M Street High School and exists today as Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. AA principal of M Street High School in D.C. She joined the school as a teacher the first year it opened in 1870 and became its first African American principle shortly thereafter. She remained in Washington D.C. until her death in 1894, contributing to other women’s causes like the Colored Women’s League of Washington, D.C.

Lucy Laney

Like Mary Jane Patterson, Lucy Laney was a “first graduate,” this time from the prestigious Atlanta University, now Atlanta Clark University. Laney was born on April 13, 1854 (so we are technically celebrating her birthday!) to Louisa and David Laney in Georgia. Though she was born during the period of slavery, her father had purchased his and her mother’s freedom prior to Laney’s birth so their child was born free. Lucy was a gifted student and could translate texts written in Latin as early as twelve years old. She attended high school in Macon and enrolled in the first class at Atlanta University in 1869. She graduated from their Normal Department, which was a teacher training school, in 1873. Laney went on to found the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in 1886 in Augusta. The Haines Institute was not only an educational institution, but it soon became a site of African American culture in Georgia hosting lectures, concerts, and other gatherings. In addition to her role as principal, which she maintained for 50 years, Laney taught Latin at the school and helped students graduate to Fisk, Yale, and other elite institutions. The school was so successful that it was featured alongside Tuskegee Institute, Hampton Institute, Roger Williams University, and Shaw University at the Paris Exposition in 1900 and President Taft visited Haines in 1909.

Two of Laney’s most famous students, which Sue Bailey Thurman acknowledges in the cookbook are Mae Belcher and John Hope, the first Black president of Morehouse College. She was also an influential figure for Mary McLeod Bethune, who modeled her school off of the Haines Institute. Laney passed away on October 23, 1933. Her place as a leader for African Americans in Georgia was solidified when she, Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, and Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. became the first African Americans to have their portraits hung in the Georgia state capitol in 1974.

“God didn’t use any different dirt to make me than the first lady of the land.”

Lucy Laney

Elizabeth Carter Brooks

The final pioneer is Elizabeth Carter Brooks, who worked as a teacher in New Bedford, Massachusetts, her hometown, for 29 years. Alongside her work in education, Brooks was also an architect and activist for many causes in the Black communities of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Born in 1867 to formerly enslaved mother, Elizabeth graduated from New Bedford High School and went on to study architecture at Swain Free School of Design. She became the first African American graduate of New Bedford’s Harrington Normal School for teachers.

Brooks began her teaching career at an African American orphanage in Brooklyn, New York, and then moved back to New Bedford where she served as the first African American woman hired as a public school teacher in the city. She is counted among the pioneers as one who “developed the conscience of a community,” and eventually had a school, “The Brooks School” named after her.

Brooks’ broader service far outstripped her long teaching tenure. She was a social activist who organized on local, regional, and national levels in support of African American advancement. She served as secretary of the National Federation of Afro-American women, aided in the formation of the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, and served as the fourth president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. She challenged the National American Woman Suffrage Association on their exclusion of Colored Women’s Clubs, and pushed for the senate to adopt antilynching legislation.

Much like Sue Bailey Thurman and the NCNW with this cookbook, Elizabeth Brooks was deeply committed to the preservation of Black History. She formed the Elizabeth Carter Brooks Jr. Girls Club which met weekly for the education of young women in Black history. Further, Brooks loaned money to the Martha Briggs Educational Club for the purchase the home of Civil War hero William H. Carney, an African American Sergeant who received a medal of honor for his legendary persistent bearing of the American flag during the Battle of Fort Wagner.

Brooks used her architectural skills to further serve her community by building and founding the New Bedford Home for the Aged which opened in 1908. She also supervised the building of the Phillis Wheatley YWCA in Washington DC, at the request of the YWCA.

Anna Julia Cooper

Although not mentioned among these “pioneers,” this entry concludes with mentions of both Dr. Anna J. Cooper and Mrs. Mary Church Terrell. Bailey Thurman writes that as fellow educators, they would “rejoice.. in the honors we extend the ‘educators.'” Mary Church Terrell gets her own recipe elsewhere in the book, but this is our only encounter with Cooper, so we thought we should take the opportunity to share about her here!

Born Anna Haywood in August 1858 or 1859 in Raleigh, North Carolina, Haywood was enslaved. She worked initially as a domestic servant, but after gaining her freedom (seemingly during the Civil War) at the age of nine, she received a scholarship at St. Augustine’s Normal School and Collegiate Institute in Raleigh, North Carolina. This school opened for the education of the formerly enslaved, and Haywood stood out among her peers as uniquely bright and skilled.

She married a theology teacher from her school, George A.G. Cooper, in 1877, who died only two years later. Alone and self-dependent, Cooper pursued further education and enrolled at Oberlin College on, yet another, scholarship. She earned her BA by 1884, and her MA in mathematics by 1887. She went on to be a professor at Wilberforce University and her alma mater Saint Augustine’s. Eventually Cooper moved to Washington D.C to teach at Washington Colored High School.

Cooper was more than a classroom educator, and publilshed her first book: A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South, in 1892. In this book of essays she called for equal education of women, arguing that Black women’s education was essential to the racial uplift of Black Americans. Additionally, Cooper lectured across the country on issues of civil rights and education.

Throughout her long career, Cooper co-founded/served mulitple organizations that promoted black civil rights, including: the Colored Women’s League (1892), a “colored” branch of the YWCA, and served on the board of the first Pan African Conference (1900).

Despite her expansive contributions, Cooper consistently prioritized education. This lead her to serve as principal of M Street High School, a school for Black children in Washington, D.C. In a city where the white school board believed industrial education to be best suited for Black children, Cooper ruffled feathers by focusing on college preparation. She eventually resigned and went on to purse her doctorate first at Columbia University, but ended up completing it at the University of Paris, France. Completing her doctorate by 1925, at the age of 67, Cooper became the fourth African American woman to obtain a doctorate of philosophy.

“the cause of freedom is not the cause of a race or a sectm a party or a class- it is the cause of human kind, the very birthright of humanity. ”

Anna J. Cooper

Dr. Gertrude Rivers

Dr. Gertrude Rivers, a “life member” of the NCNW, submitted the spiced tea recipe that we made this week, so we thought we should introduce her to you all, too!

Born in Camden, South Carolina, to a methodist minister, Rivers earned her bachelor’s degree from Atlanta University, and went on to complete both her master’s and doctorate at Cornell University.

Dr. Rivers served as a professor of English and English literature at Howard University (1939-1973), after teaching at Talladega College in Alabama in 1925. She also taught at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro for four years prior to joining the faculty of Howard University.

She was connected to Elizabeth Carter Brooks through the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA, serving on the board of directors. But, much of Rivers other work was in the realm of religion, through her deep Methodist faith. This led her to serve for almost a decade in the Women’s Division of Christian Service of the Methodist Church Board of Missions, and as a board member of the Wesley Foundation of Howard University. Further, Rivers also served on the board of the National Council of Churches of Christ, the board of managers of the United Church Women, and the board of the Foundation for the International Christian University of Japan.

THE DISH:

Ingredients

1 teaspoon whole cloves

1 inch stick cinnamon

6 cups water

2-1/2 tablespoons black tea

3/4 cup orange juice

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1/2 cup sugar

The instructions for tea were short. First, we were to add the spices to the water and bring to a boil. Personally, we would not have considered the tea to be a spice, but since the next instruction was to let it steep, we went ahead and tossed it in. So, after the water boils, the recipe says to “steep 5 minutes.” We know that black tea can over-steep, so we got nervous and decided to only let it sit for about four minutes before straining.

While this is going on, the recipe says to heat the fruit juices and sugar until boiling, stirring to dissolve the sugar. After the tea is strained, you add the juice to the tea and serve immediately.

We tried it as a hot tea and it was fine. Abena had the brilliant idea to try the tea over ice and what a difference it made! It tasted like a spicy “Arnold Palmer,” which is a cold half black tea, half lemonade drink that you can buy in a can at gas stations.

Final Thoughts

We think that the ice was a major improvement to this recipe. Full disclosure, it was about 80 degrees in Kayleigh’s apartment when we made the tea, so that may have contributed to our general indifference to a hot beverage, but we do think that the iced version would be better regardless. Plus we’re in the South, so iced tea serves as our version of “afternoon tea.”

Notes

Mary Jane Patterson (Black Past)

Lucy Laney (New Georgia Encyclopedia)

E. Stanly Godbold J. Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter : The Georgia Years, 1924-1974. Oxford University Press; 2010.

Elizabeth Carter Brooks

Anna Julia Cooper

Gertrude Rivers